Response to the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act Implementation Request for Comment

The Honorable Alan Davidson

Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Communications and Information and NTIA Administrator

+

National Telecommunications & Information Administration

U.S. Department of Commerce

1401 Constitution Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20230

+

RE: Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act Implementation Request for Comment [Docket No. 220105-0002]

+

Dear Assistant Secretary Davidson:

CEO Action for Racial Equity (CEOARE) is pleased to submit our response to your Request for Comment. We aim to provide input and recommendations for consideration in the development of broadband programs established by the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) for implementation by National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA). We commend you for recognizing the value of closing the Digital Divide as a modality to directly address racial disparities and improve the lives of historically marginalized and disadvantaged groups.

CEOARE is a Fellowship composed of over 100 companies that mobilizes communities of business leaders with diverse expertise, across multiple industries and geographies, to advance public policy in four key areas — healthcare, education, economic empowerment, and public safety. Our mission is to identify, develop, and promote scalable and sustainable public policies and corporate engagement strategies that address systemic racism, social injustice, and improve societal well-being.

In evaluating historically underserved populations, the CEOARE Fellowship has a policy portfolio focused on eight issues that disproportionately and systemically impact Black Americans, including Closing the Digital Divide. Our comments are grounded in a principles-based approach which has relevance across several topics within this Request for Comment and which are of critical importance to Black Americans and communities of color, including:

- Accessibility: In urban and rural communities, access to a reliable broadband network will help enable full participation in society and strengthen the U.S. economy.

- Affordability: Even when broadband is available, it must be affordable for moderate to low-income Americans.

- Adoption: Barriers to technology adoption should be understood and addressed to help enable all to benefit from digital connectivity.

- Data Mapping and Tracking: Accurate data mapping is necessary to understand the intersection between racial equity and the Digital Divide.

Comments on the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act Implementation

-

What are the most important steps NTIA can take to ensure that the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law’s broadband programs meet their goals with respect to access, adoption, affordability, digital equity, and digital inclusion?

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted more than ever how essential broadband is to the future of American life, education, jobs, health and medical care. There are multiple facets to the Digital Divide, including an inability for families to afford broadband even where it exists; a lack of physical infrastructure to access the internet; or substandard infrastructure.[1]The Digital Divide in America is heavily interwoven with issues of race, education, and economic status. Black Americans remain less likely than non-Hispanic white Americans to own a traditional computer or have high-speed internet at home.[2] Additionally, a recent study concluded that Black Americans are ten years behind white peers in digital literacy and could be disqualified or underprepared for 86% of the jobs in the U.S. job market by 2045.[3]We recommend targeting a certain percentage of fund allocations as well as implementation resources to communities of color. This will make a significant impact on Closing the Digital Divide and will improve millions of Black Americans’ lives for the better.

To meet the goals of access, adoption, affordability, digital equity, and inclusion, we recommend that the NTIA view implementation of the law with a racial equity lens so that Black Americans in both served and underserved areas are benefited by the law’s implementation.

-

Obtaining stakeholder input is critical to the success of this effort. How best can NTIA ensure that all voices and perspectives are heard and brought to bear on questions relating to the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law’s broadband programs? Are there steps NTIA can and should take beyond those described above?

It is critical to consider stakeholder input in both unserved and underserved areas in an equitable manner. The Digital Divide is usually framed as a “rural” issue due to substandard or no broadband infrastructure in remote areas. However, urban communities, including many Black communities and low-income households, are also deeply affected by inadequate and/or outdated broadband infrastructure.The Digital Divide is a significant issue for Black Americans in both urban and rural areas. Approximately five million Black Americans in urban areas are without access to broadband.[4] In rural counties, broadband availability is almost 20 percent lower where a majority of residents are Black compared to rural counties that are predominately white.[5] Overall, 36.4% of Black households do not have a computer or broadband access.[6]Equitable input from both unserved and underserved areas will also enable grassroots organizations in historically marginalized areas, both urban and rural, to have a voice in the implantation process so that the digital needs of Black Americans are adequately addressed in the IIJA rollout.

-

Transparency and public accountability are critical to the success of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law’s broadband programs. What types of data should NTIA require funding recipients to collect and maintain to facilitate assessment of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law programs’ impact, evaluate targets, promote accountability, and/or coordinate with other federal and state programs?

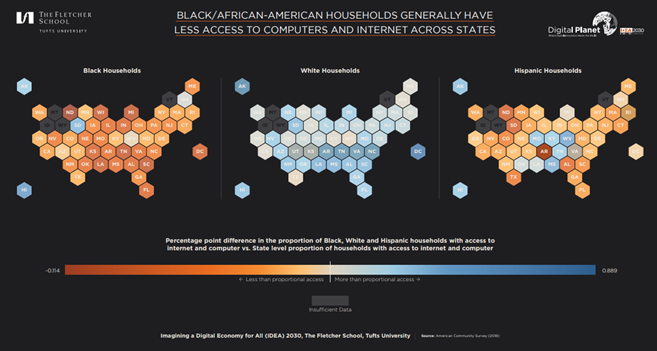

Race-based data is currently not an enumerable factor in the IIJA. For example, the law relies on FCC data maps to identify unserved and underserved areas. However, the FCC does not collect disaggregated data on Form 477 so it can be difficult to track the number of Black Americans and communities of color who do not have access to broadband.Disaggregated racial data is crucial in uncovering and addressing disparities in broadband access. We urge you to consider other sources of broadband access data, including state-sourced data and data from public-private partnerships that account for race so that implementation solutions can be targeted to maximize impact in assisting communities of color.For example, using disaggregated racial data from the U.S. Census Bureau [7], the Fletcher School at Tufts University illustrates where the digital connectivity gaps persist for Black Americans at the state level:[8]

+

-

Broadband deployment projects can take months or years to complete. As a result, there are numerous areas where an entity has made commitments to deploy service – using its own funding, government funding, or a combination of the two – but in which service has not yet been deployed. How should NTIA treat prior buildout commitments that are not reflected in the updated FCC maps because the projects themselves are not yet complete? What risks should be mitigated in considering these areas as “served” in the goal to connect all Americans to reliable, affordable, high-speed broadband?

We acknowledge the difficulty in determining how to treat projects not yet reflected in FCC maps. In making this decision, it is important to consider the specific risk of determining an area as “served” without deeper investigation and confirmation as to the accuracy of connectivity, especially in Black communities and communities of color.

U.S. cities and urban counties have many residents who lack home broadband service. Specifically, 13.9 million metropolitan households live without an in-home or wireless broadband subscription.[9] For comparison, this is more than triple the 4.5 million rural households without a broadband subscription.[10] Many urban low-income neighborhoods including public housing units were not historically considered when initial broadband infrastructure was constructed and continue to lack reliable service today.

Structural limitations and housing insecurity are also risks to closing the Digital Divide. In a BCG and Comcast[11] survey of 1,500 low-income households, approximately 15% of correspondents were unable to access internet services because of housing-related challenges. In the study, one organization reported, “We’ve got a lot of ‘unofficial’ apartments in the city…. It might be a basement unit or one located in what’s technically labeled as a single-family home.” ISPs may not offer the option of installing a second wireline service into a single-family home.

The study also states that, “low-income households have experienced higher-than-usual levels of housing insecurity during the pandemic. Transience deters people from investing time in setting up internet service.”[12] Even in urban areas with high levels of broadband access that may be considered as “served” based on data maps, low-income families are still three times as likely to lack access as the wealthiest urban families.[13]

Accuracy and confirmation of “served” areas will help mitigate the risk of disconnected housing units, city blocks and even entire neighborhoods from being left out of IIJA implementation. This will provide all Americans, regardless of race and geographic location, access to a reliable broadband network to fully participate in society and contribute to the growth of the U.S. economy.

-

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law includes historic investments in digital inclusion and digital equity, promising to bring all Americans the benefits of connectivity irrespective of age, income, race or ethnicity, sex, gender, disability status, veteran status, or any other characteristic. NTIA seeks to ensure that states use Digital Equity Planning Grants to their best effect. What are the best practices NTIA should require of states in building Digital Equity Plans? What are the most effective digital equity and adoption interventions states should include in their digital equity plans and what evidence of outcomes exists for those solutions?

As a leading practice, State governments could each form a central body responsible for leading and coordinating interagency and state-level digital inclusion activities. Digital inclusion activities may vary from state to state but could include addressing broadband affordability, broadband access, and barriers to technology adoption, such as digital literacy training and IT support for low-income families. A digital equity office would establish a Digital Equity Plan in coordination with relevant community organizations to address how to close the Digital Divide permanently within their jurisdiction.The state digital equity office’s roles and responsibilities could typically include: leading the coordination of digital inclusion activities on behalf of the state, assisting in the development of digital equity policy, coordinating funding, strengthening local digital equity ecosystems, educating policymakers, local governments, and stakeholders on digital equity and inclusion, guiding digital equity focused research and data use, and piloting scalable digital inclusion models.[14] A digital equity office would increase the likelihood that every resident—regardless of income, race, ethnicity, or any other demographic characteristic—can subscribe to a reliable broadband service.[15]

-

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law requires state and territories to consult with historically marginalized and disadvantaged groups, including individuals who live in low-income households, aging individuals, incarcerated individuals (other than individuals who are incarcerated in a Federal correctional facility), veterans, individuals with disabilities, individuals with a language barrier (including individuals who are English learners and have low levels of literacy), individuals who are members of a racial or ethnic minority group, and individuals who primarily reside in a rural area. What steps should NTIA take to ensure that states consult with these groups as well as any other potential beneficiaries of digital inclusion and digital equity programs, when planning, developing, and implementing their State Digital Equity Plans? What steps, if any, should NTIA take to monitor and assess these practices?

In order to make certain that State Digital Equity Plans include the voices of historically marginalized and disadvantaged groups, we urge you to ask states to consult with local grassroots and community-based organizations, who are helping to close the Digital Divide firsthand. These organizations are key to the equitable disbursement of resources into the communities and homes that need it the most. Different unserved and underserved areas, both urban and rural, may have different needs in addressing digital equity gaps.For example, some communities may have issues with digital literacy, while others may have low adoption rates due to affordability issues and the lack of promotion of low-income subsidies and plans. Place-based organizations will have much better pulse on community issues than governmental agencies alone, enabling states to better target disadvantaged populations with creative solutions.

When it comes to trust, there is no substitute for the connections that local, grassroot organizations have in a community. A few examples from a recent Brookings study include:

• Portland, Oregon built a Digital Inclusion Network to empower communities to bridge the Digital Divide. They brought in a diverse, countywide, and community-based work group as well as engaged the community and neighborhood leaders on the development and implementation of their Digital Equity Action Plan.

• San Francisco conducted a citywide survey with over 1,000 residents as part of its Digital Equity Strategic Plan, followed by a community-needs assessment with over 400 participants at community fairs, affordable housing meetings, food pantries, schools, and community centers. They focused deeply on integrating with the community, including approaches that build the digital capacity of community-based organizations, support community-led innovation challenges, and continuously collect community feedback.

+

Conclusion

We appreciate that NTIA is looking for opportunities to improve the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act implementation of broadband programs. We hope our responses convey our enthusiastic interest in advancing racial equity priorities that seek to close the Digital Divide. Please do not hesitate to contact Roz Brooks via email at roslyn.g.brooks@ceoactionracialequity.com to discuss further or if you have any questions.

Sincerely,

CEO Action for Racial Equity

+

Citations

- Titilayo Tinubu Ali, Sumit Chandra, Sujith Cherukumilli, Amina Fazlullah, Elizabeth Galicia, Hannah Hill, Neil McAlpine, Lane McBride, Nithya Vaduganathan, Danny Weiss, Matthew Wu, “Looking Back, Looking Forward: What It Will Take to Permanently Close the K–12 Digital Divide”, Boston Consulting Group & Common Sense Media, 2020.

- Sara Atske and Andrew Perrin, “Home Broadband Adoption, Computer Ownership Vary by Race, Ethnicity in the U.S.”, Pew Research Center, July 16, 2021.

- Apjit Walia, “America’s Racial Gap & Big Tech’s Closing Window”, Deutsche Bank, September 2, 2020.

- Bill Callahan and Angela Siefer, “Limiting Broadband Investment to “Rural Only” Discriminates Against Black Americans and Other Communities of Color”, National Digital Inclusion Alliance, June 2020.

- Rep. G.K. Butterfield, “Race and the Digital Divide: Why Broadband Access is More than an Urban vs. Rural Issue”, The Hill, May 13, 2019.

- The Digital Divide: Percentage of Households by Broadband Internet Subscription, Computer Type, Race and Hispanic Origin, United States Census Bureau, September 11, 2017.

- 2018 American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau.

- Digital Injustice, The Fletcher School at Tufts University, June 22, 2020

- Lara Fishbane and Adie Tomer, “Neighborhood Broadband Data Makes it Clear: We Need an Agenda o Fight Digital Poverty”, The Brookings Institution, February 6, 2020.

- Lara Fishbane and Adie Tomer, “Allan Holmes, Eleanor Bell Fox, Ben Wieder and Chris Zubak-Skees, “Rich People Have Access to High Speed Internet; Many Poor People Still Don’t”, The Center for Public Integrity, May 12, 2016.

- Chris Goodchild, Hannah Hill, Matt Kalmus, Jean Lee, and David Webb, “Boosting Broadband Adoption and Remote K–12 Education in Low-Income Households”, Boston Consulting Group, May 12, 2021.

- Chris Goodchild, Hannah Hill, Matt Kalmus, Jean Lee, and David Webb, “Boosting Broadband Adoption and Remote K–12 Education in Low-Income Households”, Boston Consulting Group, May 12, 2021.

- Allan Holmes, Eleanor Bell Fox, Ben Wieder and Chris Zubak-Skees, “Rich People Have Access to High Speed Internet; Many Poor People Still Don’t”, The Center for Public Integrity, May 12, 2016.

- Amy Huffman. “Defining a State Digital Equity Office: Recommendations for States as They Assume Digital Inclusion Work”, National Digital Inclusion Alliance, March, 2021.

- Adie Tomer and Lara Fishbane, “Bridging the Digital Divide Through Digital Equity Offices”, The Brookings Institution, July 23, 2020.